Attending the Airline Information Mega Event wasn’t actually that interesting to a travel writer. Not on the surface. There were important executives there who ordinarily hire underlings to talk to people like me, and though I got to sit in on conference sessions they were often filled with jargon and obscure ideas about how they should run their businesses.

But in the process of listening to these people peak, I also learned some interesting information that can shed light on why program devaluations happen and some of the complex thinking that goes on behind the scenes. These people aren’t exactly heartless. They travel a lot, too, and have their own status and points balances. I heard “FlyerTalk” mentioned several times during discussions.

One panel member went so far to say that an award chart is a promise to program members and that devaluing the award chart means breaking that promise. Others pointed out, as I have, that in some cases award charts need to be inflated if points are earned and redeemed based on spend, a feature of most hotel loyalty programs. I’m spending more per night and earning more points. Obviously the cost of the hotel where I stay for free is also increasing, so it’s natural that I have to redeem more points. View from the Wing calculated that Hyatt’s recent devaluation works out to only 4% on average — and on an annual basis, Gold Passport’s inflation is less than that of the U.S. dollar.

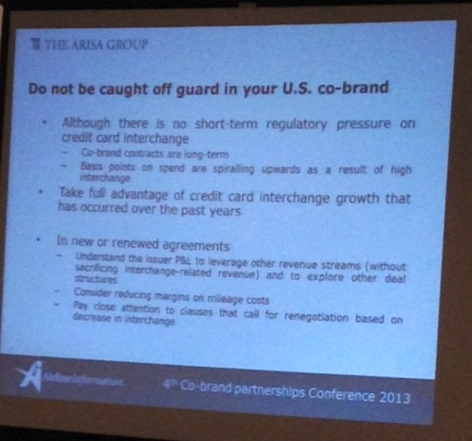

Miles issued through credit cards are definitely one concern. Co-branded credit cards can be big money. An entire session covered regulatory pressures on issuing banks, particularly the decrease in transaction interchange fees outside the U.S. Though we Americans are safe for now, we can already see the consequences for miles-earning debit cards. Banks earn less money on every purchase, which means they have less money to pay the airlines.

While you might say, “Great! Fewer miles in circulation means less risk of award chart inflation!” it’s also possible that things are worse than they appear on the surface. The bank may be awarding fewer miles per dollar, but it might also be paying the airline less for those few miles it still buys. When miles are too cheap, regardless of how many are being issued, it may no longer be affordable for the airline to offer award space.

Breakage is another important consideration. This describes miles that expire or are otherwise wiped off an airline’s liabilities. One example was provided for Delta Air Lines. In 2012, frequent flyer miles were the third largest liability on their balance sheet. They make very careful estimates of how much breakage they can expect from their customers because if they are off by 1%, it costs them $30 million dollars! It doesn’t necessarily mean the airline wants to make it difficult for you to use your miles, but they need to be very sure that they can model account balances predictably.

So let’s switch to some good news. Well, maybe not good news, but certainly less depressing.

The fraction of award travel on an airline is a useful measure of a loyalty program’s health. A range of 2-4% is seen as a reasonable benchmark, though it obviously depends on the nature of the airline, its loyalty program, and other strategic factors. If this number drops to 1%, meaning more people are paying for travel with cash, it means the customer doesn’t see value in your loyalty program — not good, despite the extra money in the short-term. Eventually there may not be anyone willing to pay with cash, either. So an airline won’t try to make things too difficult.

Travel Is Free has a good example of poor award availability and makes the case that such situations required United to devalue it’s award chart — it’s a combination of profitability and customer engagement with the brand. The same executives at the conference who were talking about award charts as a promise to the customer were also saying that it’s important to encourage the first redemption as soon as possible. If you keep raising the bar and make it impossible to save up, customers lose faith. This is why United didn’t touch its 25,000-mile domestic awards (even though they make up the vast majority of their customers’ redemptions) and why many credit cards offer a sign-up bonus that can immediately provide a low-level redemption.

Award travel can reach levels as high as 8%, too, but programs usually become unprofitable without significant outside funding (e.g., from a bank or other partner). There are, in fact, a lot of ways that a program can maintain profitability and the value of its co-brand products without devaluing their award charts. Much of it comes down to managing costs, which shouldn’t be a surprise to those following the recent history of credit card benefits. Offering free checked baggage is seen as an easy substitute to providing triple miles. The problem, of course, is when you have customers who already get these benefits and don’t see any upside. (I’m looking at you, United Airlines.)

I’ll end with a lesson. I was never very tempted by auctions and stuff like that. Why blow 100,000 miles on a so-called “once in a lifetime” experience or some product that I can easily buy with cash? These are often horrible values. The airlines, banks, and consultants all know it. The number one recommended approach to reduce the liabilities of a loyalty program was to host an auction. It’s the cheapest way for them to part you from your hard-earned miles because they have a much better idea of their value than you do. So, don’t play that game. Just don’t.

A special thanks to PointsHound for introducing me to the conference organizers. In the interest of full disclosure, my conference fee was waived in exchange for publicizing the event on my blog. But why not? I think it’s an interesting experience to spend time with the “opposing team” insofar as we often talk about gaming loyalty programs. I am receiving no other compensation, and I have paid for my own travel expenses.